For my second project at Metis, I decided to put a twist on a classic regression problem and explore the impact of women on box office revenue.

I’ve always been conscious of the portrayal of women in film and popular culture. As a fan of sci-fi and action movie franchises, it bothers me that women are consistently underrepresented in these types of films or relegated to love interests with little to no character development.

There has been an increasing amount of media attention dedicated to the unequal treatment of women in Hollywood, most recently the gender wage gap. Movie power brokers (who are overwhelmingly men) claim that audiences don’t like movies with strong female characters, and tend to invest less in movies made by and starring women. This is distinctly unfair, and I sought to answer two main questions:

-

Can data confirm the anecdotes about gender bias?

-

Is there a financial case, in addition to the compelling social and moral reasons, for Hollywood to make more films with leading female casts and creators?

(Spoilers: Yes and yes!)

Sources and Inspiration

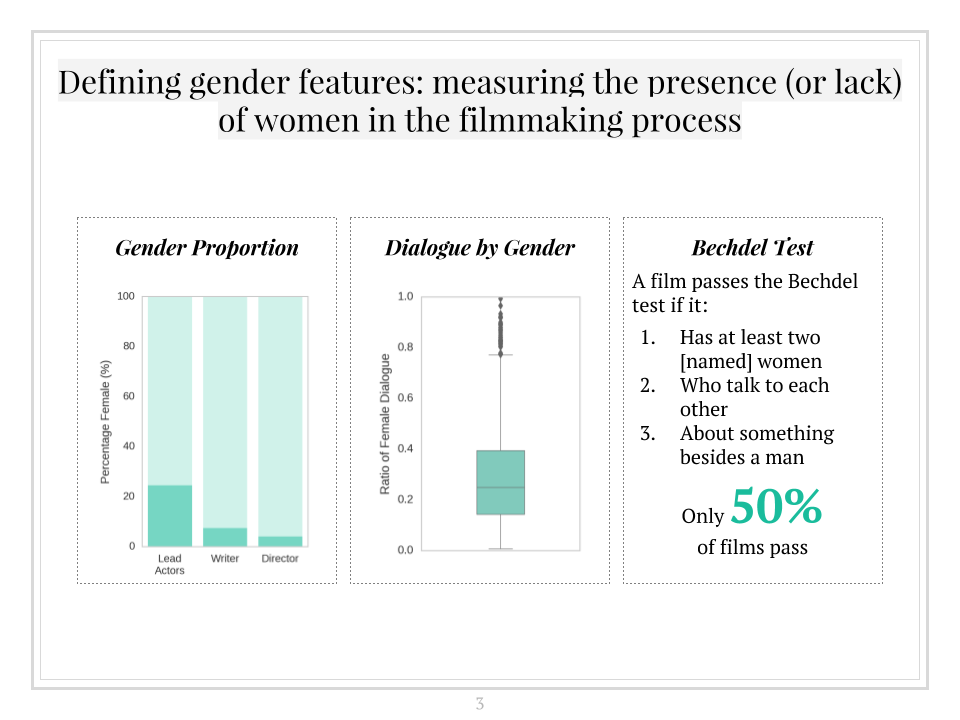

The Bechdel test (popularized in 1985 by comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For) is a simple test that has often been used to call attention to gender bias in movie making. A film passes a test if it a) has at least two (named) women in it, who b) talk to each other, about c) something besides a man. As you may imagine, a good number of films do not pass the test (currently 42.35% of the bechdeltest.com database).

The Bechdel test has its flaws – films with strong female protagonists and feminist themes occasionally fail the test (e.g., one of my favorites, Ex Machina). However, it is mostly a reliable indicator as to whether women are “humanized” if they actively drive the narrative and are not just props.

In April 2016, Polygraph, a site dedicated to data journalism, released the self-proclaimed “Largest Ever Analysis of Film Dialogue by Gender”. This included their full dataset, which listed the number of all male and female words spoken in a film, compiled from publicly available screenplays.

With both of these wonderful datasets, coupled with the vast array of movie data available from the web, I was confident that I could find the answers to my questions with data science and machine learning!

Approach and Findings

Feel free to check out my code on my github!

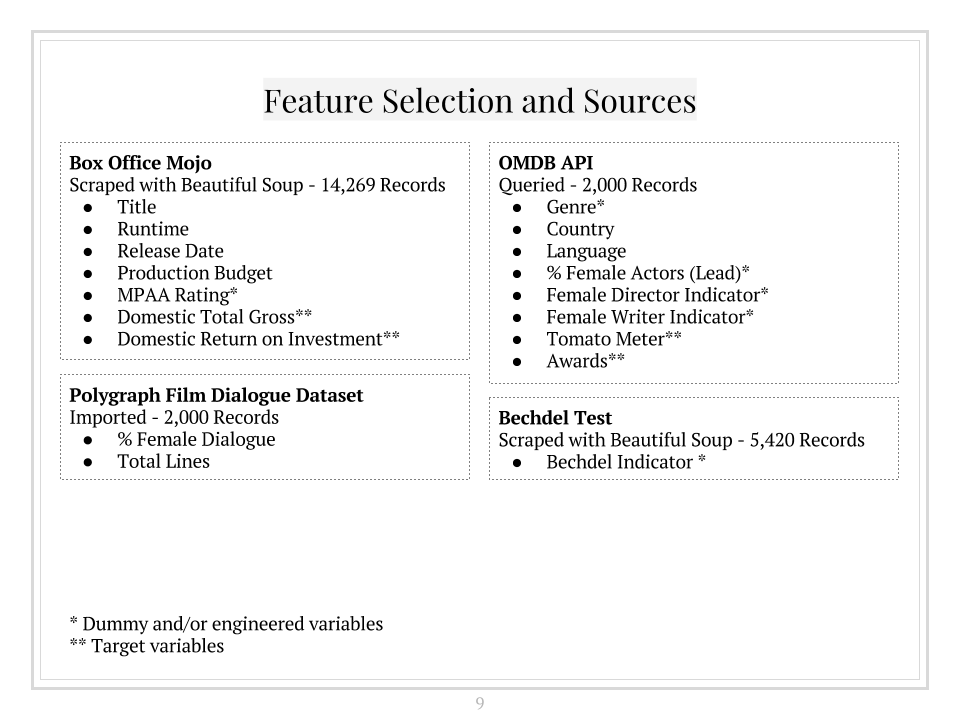

- Acquiring data - My data was acquired through a combination of web scraping, APIs and direct acquisition. All data was stored in Pandas data frames with Pickle, a library to serialize and save Python object structures.

- I started by scraping general movie data from 1980-2016 (including domestic total gross numbers) from Box Office Mojo using Beautiful Soup, a Python web scraping library. This involved a multi-step scraping process to obtain the URLs for each movie and pull individual movie data points. This resulted in records for 14,269 movies.

- I then scraped bechdeltest.com with Beautiful Soup for Bechdel test results, which resulted in 5,420 records.

- I then read in and stored the data for the 2,000 movies in the Polygraph film dialogue dataset (which Matthew Daniels has generously made available on github), aggregating the data to calculate the % of words spoken by female characters per movie.

- Finally, I queried the OMDB API for the 2,000 films in the Polygraph dataset, which helped to supplement the general movie data I had initially acquired from Box Office Mojo with more granular detail on genre, country, language, writers, directors, awards, ratings, etc.

- Data joining, munging and wrangling - After merging all 4 data sources I ended up with 1,117 complete records. While this was a far cry from my largest dataset at 14,269 records, I felt strongly that I didn’t want to include partial data given the importance of each of the data sources. Further wrangling activities included:

- Dropping overlapping columns (e.g., between those pulled from Box Office Mojo and OMDB API)

- Creating dummy variables for categorical data (e.g., Genre, MPAA rating)

- Removing duplicates

- Changing data types for dates and float values

- Identifying and removing outliers that might skew results

When all was said and done, my compiled dataset consisted of 662 records!

- Feature engineering - In addition to the cleanup activities above, I engineered features and targets such that they could be better used in the model and/or be indicative of gender. This included:

- Using the python package Genderizer to help impute the gender of the director, writer, and (lead) actors

- Using regular expressions to obtain a numerical representation of award wins and nominations, based on a text blurb

- Calculating ROI as domestic total gross over production budget, to account for the strong correlation between the two

- Exploratory Data Analysis - I wanted to see if my data would confirm if the gender bias exists in movie making. The results were stark and clear:

- From my compiled dataset, only 25% of lead actors, 7.5% of writers, and 4% of directors were female

- The median of words spoken by females as a % of total dialogue was only 26%

- 50% of films in my dataset passed the Bechdel test

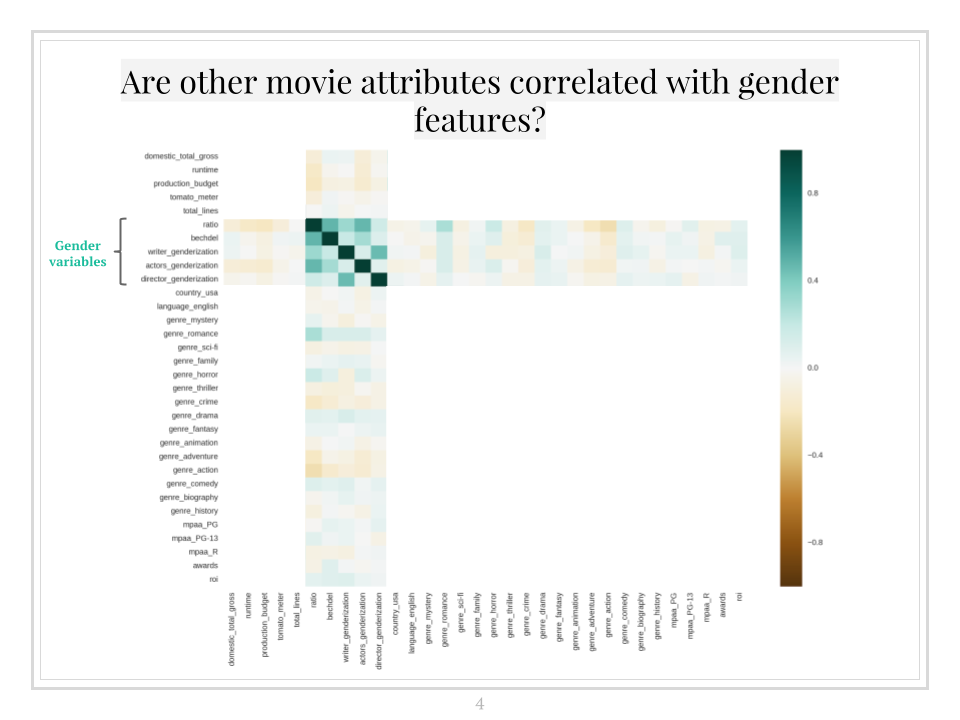

To make sure the gender impact wasn’t entirely driven by other features, I plotted a correlation heatmap to explore any potential interactions. I thought that my gender features might be highly correlated with genre, but that wasn’t the case. The gender features were all moderately positively correlated with each other; as might be expected, a film that has a high ratio of female dialogue is also probably likely to pass the Bechdel test.

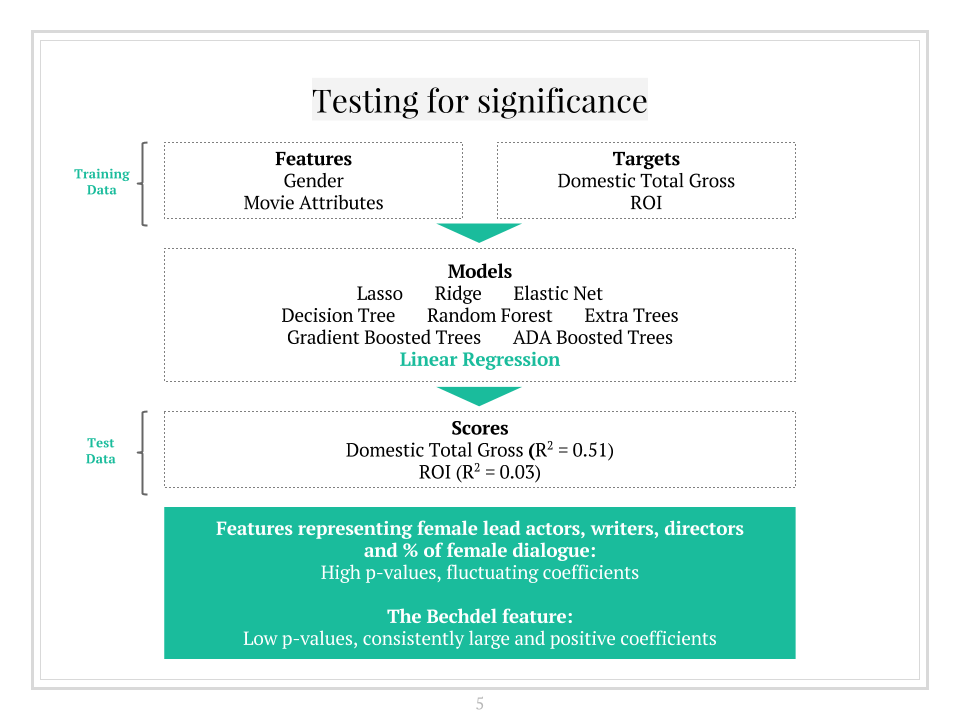

To make sure the gender impact wasn’t entirely driven by other features, I plotted a correlation heatmap to explore any potential interactions. I thought that my gender features might be highly correlated with genre, but that wasn’t the case. The gender features were all moderately positively correlated with each other; as might be expected, a film that has a high ratio of female dialogue is also probably likely to pass the Bechdel test. - Modeling - I performed several modeling iterations with different regression models and different subsets of the data, using the machine learning python packages StatsModels and Scikit-learn. I attempted to predict Domestic Total Gross, Domestic ROI, Tomato Meter (Rotten Tomatoes Rankings) and Awards Ranking (proxied by the sum of wins and nominations), where possible using grid search to optimize.

As this was a noisy (and small!) dataset to begin with, my best performing model predicting Domestic Total Gross was a linear regression model with an R-squared of .51. Regularization and the use of decision trees did not improve results. However, my models revealed important information about my features:

As this was a noisy (and small!) dataset to begin with, my best performing model predicting Domestic Total Gross was a linear regression model with an R-squared of .51. Regularization and the use of decision trees did not improve results. However, my models revealed important information about my features:

- High p values and fluctuating coefficients of the gender features - This suggests that there is no conclusive link between the proportion of female lines, female actors, writers, directors to box office returns - therefore, the assertion that women-driven films are negatively correlated with returns is false.

- Low p values and consistently large and positive coefficient of the Bechdel test feature - This suggests that the Bechdel test is statistically significant in predicting box office returns. All things held equal, my models predicted that passing the Bechdel test would increase domestic total gross by $22 million (and ROI by around .20%).

- Running the models on subsets of the data and other target variables highly correlated with returns such as awards and ratings corroborated these findings

Conclusions

Based on my results, there is no evidence to support that more lead actresses, an increased proportion of female dialogue, or films made by women lead to lower returns. With $22 million per film in domestic total gross as the cost of objectifying women, Hollywood needs to actively take a stand to increase the role of women in film!

I’m personally really looking forward to the upcoming Wonder Woman and Ocean’s Eight movies, amongst others. Ghostbusters was a step in the right direction, and I can’t wait to see more female protagonists on the big screen!

Questions about my analysis? Feel free to check out my github or send me an e-mail at neo.kaiting@gmail.com.

Leave a Comment